As the Trump administration moves forward on, or perhaps we should just say towards, its strategy for Afghanistan, the various tribes of the foreign policy and political establishment seem no closer to consensus than they have been since at least 2008. In our sixteenth year of war the lack of consensus indicates a lack of understanding and should stand as an enormous caution to all of us. On Thursday Sameer Lalwani published Four Ways Forward in Afghanistan, and this morning, on Memorial Day, the New York Times Editorial Board weighed in with The Groundhog Day War in Afghanistan. Michael G. Waltz published No Retreat: The American Legacy in Afghanistan Does Not Have to Be Defeat in War on the Rocks two weeks ago. Obviously the Times goes into less detail than Lalwani or Waltz, but nevertheless makes a clearer case. Perhaps inadvertently, the Times articulates in its penultimate paragraph the key, and insurmountable, difficulty while Lalwani chooses to ignore it when it is too inconvenient.

As the Trump administration moves forward on, or perhaps we should just say towards, its strategy for Afghanistan, the various tribes of the foreign policy and political establishment seem no closer to consensus than they have been since at least 2008. In our sixteenth year of war the lack of consensus indicates a lack of understanding and should stand as an enormous caution to all of us. On Thursday Sameer Lalwani published Four Ways Forward in Afghanistan, and this morning, on Memorial Day, the New York Times Editorial Board weighed in with The Groundhog Day War in Afghanistan. Michael G. Waltz published No Retreat: The American Legacy in Afghanistan Does Not Have to Be Defeat in War on the Rocks two weeks ago. Obviously the Times goes into less detail than Lalwani or Waltz, but nevertheless makes a clearer case. Perhaps inadvertently, the Times articulates in its penultimate paragraph the key, and insurmountable, difficulty while Lalwani chooses to ignore it when it is too inconvenient.

Lalwani’s four ways forward will be familiar to anyone who has responded to a staff college essay prompt–Statebuilding, Reconciliation, Containment, and Basing. He argues that the strategies are distinct, and indeed mutually exclusive. While each may contain elements of the others, he is correct that the United States has vacillated between the four and consequently failed at all. Strategy requires, as Lalwani states, “an honest appraisal of costs, risks, and priorities.” In fact I would reorder his list. The first concern is priorities–what end is non-negotiable or at least paramount. For which end would you sacrifice the others? In one key observation he notes that Statebuilding is incompatible with Basing, a factor with which military planners have been unwilling to grapple throughout our forever wars. Hamid Karzai’s maddening anti-Americanism was a political necessity for any Afghan politician aspiring to popular legitimacy.

Priorities, of course, can change once we determine the costs and risks. It may be that our first priority is unachievable at an acceptable cost, and this is particularly likely when engaging in a civil war in a remote and culturally alien country on the far side of the world. Afghanistan is strategically valuable for two reasons–it provides a base of operations in a volatile region where we have little presence, and it has the demonstrated potential to harbor and even nurture anti-western terrorists. Both of these advantages are real, but neither is unique or fundamentally necessary. The first is necessary only if we feel a compelling need to directly influence events in the region through military force. Accepting the limits of U.S. power in a remote area is also a viable option, though fraught with its own costs and risks. Salafist terrorists have found plenty of nurturing safe havens elsewhere since 2001, and so preventing them from using Afghanistan is of dubious value.

Statebuilding is the most ambitious of Lalwani’s suggestions, the most costly, and presents the highest potential payoff. In the minds of military planners, it achieves both of the above strategic objectives, but that is because they look at it in military rather than political and cultural terms. Lalwani himself falls into this trap, and it is worth quoting his implementation prescription to see the error:

The state-building strategy would deploy U.S. troops down to the brigade or battalion level to guide and mentor Afghan units and to signal an enduring commitment to the Afghan state. Retired officials have also argued that keeping troops in the fight will better ensure political support for aid to Afghanistan.

It is not always wrong or unwise to take things out of context. Sometimes when we are reading a long piece for the entire meaning we miss the small, specific errors that undermine the whole. Here it is obvious–Lalwani’s “statebuilding” is really security force building, and we’ve been doing that for at least seven years. It hasn’t worked because security forces are an organic part of a state and culture–they cannot be built separately, or at least good ones cannot be built separately. To build a state through the security forces means that you will end up with a militarized state, if you can do it at all. In 2014 I sat in a briefing in which the International Joint Command proudly announced that a particular kandak (battalion) had been trained to fire its howitzers. My battalion partnered with that same kandak in 2011, and we also trained them to fire their howitzers. In between, they had come apart due to poor leadership, recruiting and retention failure, a disastrous supply system, and a total lack of training management. The problem was not teaching a discreet group of Afghans to use a particular weapon, but rather trying to build a 20th century industrial army in a state that did not incorporate any of the cultural, educational, or political prerequisites. Deploying advisers down to brigade level will improve the planning and operating capability of those brigades as long as the advisers remain. It will do nothing to root out corruption, patronage promotions, rampant illiteracy, or any of the other fundamental problems.

Michael G. Waltz’s May 12 essay in War on the Rocks, No Retreat: The American Legacy in Afghanistan Does Not Have to Be Defeat, assumed the statebuilding strategy, and therefore was able to do a better job articulating the costs and risks in the space alloted. However, Waltz also assumed away crucial considerations in his otherwise clear-eyed argument for a full commitment. Waltz predicts that Secretary Mattis and Lieutenant General McMaster will successfully articulate to the president that “the key ingredient to that approach is time — most likely decades” without addressing the domestic political strategy that must accompany such a commitment. He goes on to say, “it took the Colombian government over 50 years to get to this point in its struggle with the FARC and it was arguably more advanced in its capability than the Afghan government,” without acknowledging such a precedent is likely to make the strategy politically infeasible. Waltz might argue that the president should sell the policy, but in reality he is banking on the disconnect between the military and the public. Put simply, Waltz and other advocates of statebuilding assume that a president can pursue a decades-long military and political commitment in Afghanistan, at a cost of hundreds of billions of dollars and an indeterminate number of U.S. lives, and the American people will not care enough about the Afghan war or the continued drain on the U.S. military to impose meaningful political costs. That is an open question, but counting on voter apathy leaves the president and the strategy vulnerable to a spectacular event that suddenly focuses attention.

Waltz is also more detailed than Lalwani in his examination of Pakistan’s role and the problems it creates, but he once again glosses over the fundamental problem. Waltz notes that no modern insurgency with external sanctuary and support has ever been defeated, and he argues that the U.S. government must be more coercive with Pakistan in order to gain compliance. Pakistan has calculated that the destabilization of Afghanistan and a friendly Pashtun insurgency dependent upon Pakistani largesse are in its interests. It is difficult to see how the U.S. can change that strategic calculation in the near term without destabilizing Pakistan, and Waltz’s ideas for applying pressure all run that risk. Waltz acknowledges the risk while continuing to view the situation through an Afghanistan lens, but that is the problem. We must be very clear here–no outcome in south Asia is worse than the collapse of the Pakistan government. Pakistan is a state of over 200 million people, roiling with sectarian, economic, and cultural tension, and in possession of nuclear weapons. Its government and military are corrupt, and they have fostered religious extremists as a means of maintaining internal power and destabilizing their neighbors. While tiptoeing around the Pakistan government and security forces may seem like rewarding bad behavior, it is the least bad of a set of very bad options. There is zero chance that a destabilized Pakistan government would be replaced by something better, and a high probability that it would be replaced by anarchy, civil war, an Islamist dictatorship, or some combination of the above.

Waltz does deserve credit for addressing one fatal flaw in U.S. policy to date. In arguing for U.S. advisers down to the tactical level and greater U.S. “enabler” support, he acknowledges that such a move will entail greater risk, particularly of “green-on-blue” attacks. My own experience in Afghanistan bears this out. In fact our risk-avoidance in this area is one of the clearer indicators of our lack of seriousness and the hollowness of our rhetoric. Because the U.S. military has been unwilling to accept friendly-fire casualties, we have imposed extreme measures to protect the advisors who integrate with Afghan units. Those measures raise the cost (in total personnel and mutual trust) and therefore reduce the total capability. Looked at tactically, the decisions make sense. Green-on-blue attacks gain media attention and pose the greatest near-term risk to domestic support for the Afghan mission. Viewed strategically they make no sense at all. Just over 150 coalition troops have been killed in green-on-blue attacks over more than 15 years of war. Green-on-blue attacks therefore represent a smaller proportion of deaths than accidents and suicides. To be blunt, a military operation that is not worth 10 deaths per year is probably an operation the United States should forego. If the mission in Afghanistan is truly necessary for American defense, then we should be willing to accept a doubling or trebling of the green-on-blue casualties without a thought. The perception that we are not willing to accept it is precisely the reason we should question the political will to embark on a decades-long statebuilding enterprise.

On reconciliation, Lalwani hits the key point–a reconciled Afghanistan in unlikely to be friendly or helpful to the United States. Looking at our two strategic advantages, an Afghan government that incorporates Taliban leaders would almost certainly devolve a great deal of local control. Pashtun leaders in Kandahar, Helmand, and elsewhere would be just as likely to provide safe haven to Salafist terrorists as the Taliban government was in the 1990s. Moreover, they would continue to make more. Such a government would almost certainly provide safe havens for the Pakistani Taliban, thereby ramping up regional tensions. No Taliban-inclusive government can be expected to permit continued U.S. presence. It is difficult to see what the U.S. gains from “deep reconciliation” or how we can achieve “shallow reconciliation” as Lalwani describes it. The Taliban has shown little willingness to surrender regardless of losses, and they are currently advancing in their key territories. A few thousand American advisers will not fundamentally alter that calculus, at least not for very long.

Basing presents a tempting target for U.S. military planners who, to their credit, view Afghanistan in the broader regional context. We cannot reiterate enough–Afghanistan itself is of no value to the U.S. Unfortunately, military planners tend to see the world through the lens of military plans and either wish away the political and cultural factors or leave it to others to “set the conditions.” Bases do not exist in a vacuum. They must be both supplied and defended. Afghanistan provides the ability to put U.S. assets in close proximity to the “‘Stans,” Pakistan, and eastern Iran–a tempting capability. The problem is keeping those bases secure and supplied. A reconciled Afghan government is unlikely to permit them. An Afghan government that permits them cannot gain the legitimacy it needs to be an independent state–you cannot build your independence on obvious dependence. As much as the planners at CENTCOM may want Afghan bases, they tend to ignore the problems of keeping Afghan bases, and more importantly the problems associated with losing the Afghan bases when/if the wheels come off.

That leaves us with only containment. The dangers of Afghanistan are not that great that we cannot contemplate withdrawal. Indeed, the greatest risks are political–a U.S. president must be the one to “lose Afghanistan.” This is where we run headlong into the great tragedy of Trump and Trumpism. Had the president been more knowledgeable and better advised, he could have railed in the campaign against the “stupidity” of the previous administration’s surge and continuing commitment. He could have attacked President Obama not for pulling out but for failing to pull out fast enough. Then as president he could have continued the withdrawal while holding out delays as an incentive for desired behavior by the Afghan government. Afghanistan presented Trump with an opportunity for a bold foreign policy move that would have fit within his campaign message and divided the foreign policy establishment. A precipitous Trump withdrawal would have outraged the neocon wing of the Republican Party, whom he outraged anyway, and placed Democrats in the awkward position of either arguing for continued military engagement in Afghanistan or supporting Trump.

The greatest tragedy of all, however, is the inevitable rehashing of this argument down the road. We do not have to “lose” in Afghanistan unless we choose to. The United States has ample power to maintain a presence and stave off total defeat in and around Kabul without massive U.S. casualties or a budget-busting investment. It is doubtful that we have the capability to “win” in any meaningful way (a subject for another post), and so staving off defeat just prolongs the inevitable and leaves the most painful choice for a future president. Barrack Obama, a model of maturity and responsibility, nevertheless kicked the can. Donald Trump, a model of immaturity and irresponsibility, squandered a unique opportunity to turn Afghan withdrawal into a political win and is unlikely to take upon himself the costs of withdrawing absent some obvious and immediate payoff. Let us hope, then, that we have this conversation in 2020 as part of electing the next president, rather than in 2021 as that new president weighs the long-term and unquantifiable benefits of an Afghan containment strategy against the immediate and painful costs.

Why We Lost: A General’s Inside Account of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars

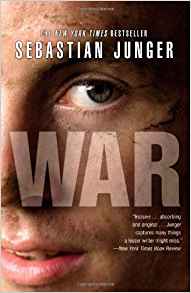

Why We Lost: A General’s Inside Account of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars WAR by Sebastian Junger.

WAR by Sebastian Junger.