This post first appeared on the Center for Security Policy Studies blog https://csps.gmu.edu/2020/03/09/to-serve-or-not-to-serve/ on March 9, 2020.

Prospective national security professionals may be forgiven for avoiding the federal government in the current political climate. Watching President Trump, members of Congress, and cable TV personalities impugn the integrity, competence, and patriotism of national security officials does not paint a picture of a happy, fulfilling career. Disapproval of administration policies, like family separation or the President’s pardoning of accused war criminals, further discourages recruiting. Nevertheless, young people with talent, integrity, and an interest in national security should pursue opportunities to serve.

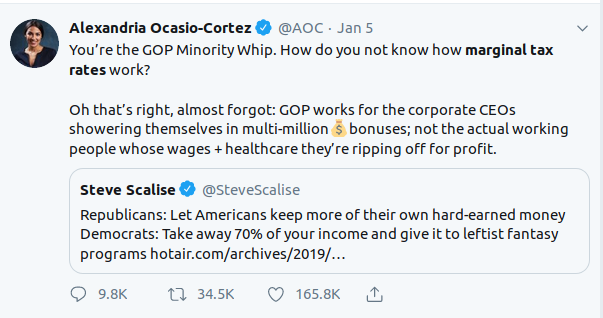

National security professionals recognized early that President Trump’s approaches to both national security and the federal workforce would pose staffing challenges. Dan Drezner wrote four Washington Post columns on the subject (see here, here, here, and here). Eliot Cohen initially encouraged people to seek positions but to “keep a signed but undated letter of resignation in their desk” to remind themselves of the requirement to identify their ethical redlines and to resign if required to violate them. He quickly reversed himself after deciding the administration would make honorable service impossible. Benjamin Wittes argued senior professional staff should stay on to ensure high quality professional advice unless ordered to do something unethical.

What has happened in the three years since these questions began circulating?

Nothing good.

The number of applicants taking the Foreign Service exam dropped by 34% in 2017 and a further 22% in 2018. President Trump appointed a high percentage of political supporters to ambassadorships, and Trump-appointed ambassadors are removing their career deputies at an alarming rate. Career prosecutors at the Department of Justice quit the Roger Stone case in response to political pressure, and the Attorney General initiated investigations of the FBI and Hillary Clintonwhile cooperating with the president’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, to produce political dirt on Joe Biden. The president personally attacked career diplomats and military officers who obeyed congressional subpoenas.

This hostile climate is exactly why talented young people of high ideals and integrity should seek careers in national security now and why more senior public servants should encourage them to do so. The most important feature of the U.S. national security apparatus is its non-partisan professionalism, while the most dangerous feature of the current administration is its disregard for the norms of American governance.

The antidote to personalization of the bureaucracy is not abstention or “deep state” resistance. National security professionals can best ensure the continuation of America’s proud tradition of non-partisan service by maintaining high professional standards while remembering Eliot Cohen’s exhortation to identify redlines. National security professionals who value our professional norms should be seeking out talented young people and recruiting them to serve.

Administration hostility is creating vacancies as more senior people choose to depart, giving young staffers opportunities to serve in responsible positions at younger than normal ages. Public service attracts people who value making a difference over personal gain, but that does not mean public servants lack ambition. Rather, their ambitions often focus on achieving good policy outcomes along with personal advancement. The former may be difficult in an administration that does not value professional expertise, but that difficulty can, paradoxically, help young staffers develop greater expertise. To have any chance of making good policy, their proposals will have to be more tightly reasoned and carefully supported than might be the case with friendlier political appointees.

Indeed, serving under a difficult administration may actually have positive side effects. New professionals can build the habit of executing policy dispassionately, at the direction of elected leaders, as well as the courage to explain and advocate policies that may not be popular with superiors. Professional staffers serving inexperienced and erratic decision-makers can unlearn some of the bad habits that their elders adopted, like presenting throwaway courses of action to limit superiors. A national security professional who begins in this environment and endures with her integrity intact is likely to be a formidable policy-maker in the future.

Finally, nobody should ever enter public service without a sense of duty, and duty does not end because the administration is hostile or incompetent. If anything, weak political appointees increase the duty of competent public servants to do their best within their ethical boundaries. Anyone hoping to have a career in national security should understand that she will have to serve in administrations with which she disagrees and under leaders of whom she disapproves. A young graduate entering public service in 1980 during the Carter administration and serving 40 years would have also served under Presidents Reagan, GHW Bush, Clinton, GW Bush, Obama, and Trump. Secretaries of State would have ranged from Al Haig to Madeline Albright. Given that broad diversity, any public servant could expect to disagree with some or even many of the people she would have to serve and policies she would have to implement. New staffers, however, have more to gain and less to lose in the current environment. Even with accelerated responsibility they will be farther from the political appointees than their more senior colleagues. Signing that letter of resignation in the desk drawer will cost them less than a mid-grade staffer who is halfway to retirement.

People who value rational, evidence-based, morally defensible national security policy can either enter the arena with their eyes open, or they can cede those entry level positions to people of lesser qualifications and greater ethical flexibility. Today is the perfect time to join, knowing that it may be a trial by fire.

am Collins (first published 1936)

am Collins (first published 1936)