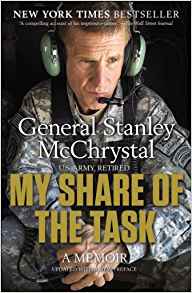

My Share of the Task: A Memoir by Stanley McChrystal

My Share of the Task: A Memoir by Stanley McChrystal

Kindle Edition, 464 pages. Published January 7th 2013 by Portfolio. ASIN B007ZHCEN2

When Stanley McChrystal commanded the special operations task force in Iraq, he sent liaison officers to all of the major conventional commands, young majors and lieutenant colonels whom he hand-picked for their intelligence, their confidence, and their understanding of and links within his task force. Some of them were steely-eyed operators from Task Force Green, and others were chemical corps officers or signaleers from his staff. The common denominator was his level of trust in them, and he empowered them with unlimited direct access. In 2008, his liaison officer to my organization was a disheveled, slightly roly-poly naval officer, and my general–deeply committed to hierarchy and physical appearances–viewed and treated him as an insignificant minion. Each night we would brief my general face-to-face on the fight against both al Qaeda in Iraq and the various Shia militias, and my general would heap scorn and abuse on “Gilligan,” the derisive local nickname for the liaison officer. “Gilligan” would take it all quietly and professionally, and then retreat to his little plywood cubby, like Harry Potter under the stairs, and call directly to then Lieutenant General McChrystal at his desk and have a 20-30 minute conversation about our share of the task. McChrystal really did flatten his organization, and he had a remarkable facility for choosing and trusting competent subordinates as individuals rather than assessing everyone against the same cookie-cutter model.

Stanley McChrystal wouldn’t know me from a random panhandler, but I know him well. Or rather, I have a clear perspective from the view of a junior staffer who watched him work and spent 20-hour days for nearly two years working with his organization. His views on leadership, counterterrorism, and our national security establishment carry great weight for those of us who watched him and his outfit in action. Watching him lead a video teleconference at 2:00 in the morning bringing together multiple military and civilian organizations to achieve a common purpose was both a pleasure and an education. McChrystal’s subordinates were fiercely loyal to this notoriously challenging task-master. He demanded much and only retained those who consistently delivered. They would, and did, follow him into hell knowing he would resource their mission, back their honest mistakes, and never, ever, squander their lives.

It is, therefore disappointing that the majority of his memoir is so banal. I began the book in a state of near hero-worship for perhaps the finest senior leader I saw in action in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I interpreted his comments in the introduction as a preview of thoughtful evaluation and tough talk to come. Instead, My Share of the Task is a workmanlike recounting of a story that has already been told. McChrystal is far too gentlemanly to name names or air dirty laundry. The very characteristics that make him an extraordinary leader preclude him from dishing the dirt. Having ended his career precipitously due to excessive candor with a journalist, he is not likely now to be more open, and he is not the sort of man to bear grudges or settle scores.

That left him with two choices, and he chose the road more traveled. McChrystal could have used his reputation and his personal experience at the very heart of the Global War on Terror to build a strong analytical case for what we should have done, what we did, and what we should do going forward. Instead he tells the story of the fight against al Qaeda in Iraq at the very tactical level. Creating an overall strategy was not McChrystal’s share of the task, and he should not be held accountable for failing to do it, but his title indicates that his book will stay firmly “in his lane” and therefore fail to provide much new or enlightening material. He then falls into the trap of personalizing the fight against AQI as a fight against Abu Musab al Zarqawi, a view belied by the recent rise of the Islamic State under Zarqawi’s successors. Zarqawi’s death and the slaughter of mid-level AQI leaders in 2007 and 2008 dampened the violence and opened a geographic and temporal space for reconciliation, but the rise of al Baghdadi and IS shows that the grievances and viciousness of the Iraqi Sunni extremists was far larger and more entrenched than any single leader. The AQI emirs of 2008 were low-grade street thugs, a few murderously clever, but mostly just violent sociopaths with no particular charisma or organizational acumen. The fuel for their insurgency, however, remained. If anything, the Maliki government stoked the fire.

McChrystal’s focus on AQI also demonstrates the strategic blindness of the entire U.S. Iraq operation. By 2007, Shia militias and Iranian influence posed at least as great a long-term threat to U.S. interests in the region as Salafist extremism. Yes, AQI and Zarqawi were stoking the fires of sectarian hatred, but that fire was dangerous to the U.S. specifically because it opened the path for Iranian influence. Zarqawi’s fatal miscalculation stemmed from his combination of psychotic violence with poor math skills. There was no way the Sunnis in Iraq could prevail once the Iranian-backed Shia militias were armed and supported by the Republican Guards Quds Force. There were too many Shias with too many weapons, and they were willing to fight. Toppling and suppressing them posed a much greater challenge than keeping them fragmented and suppressed had under Saddam. Although one element of McChrystal’s task force focused exclusively on Shia militias, and even though those militias posed the greatest threat to U.S. forces by the end of 2007, McChrystal pays them insufficient attention. He fails to step back and look not at whether his task force did a good job of fighting AQI (they did) but rather at whether the U.S. was focusing its efforts in the right direction.

McChrystal gets closer to a valuable analysis when he describes his early days as COMISAF/ COMUSFOR-A in Afghanistan, but then he slips into the can-doism that makes it so difficult for senior military commanders to provide useful advice to our civilian masters. McChrystal holds Hamid Karzai in far higher regard than any other American official. He illustrates the mission creep that made any reasonable vision of “success” or “victory” in Afghanistan impossible, but he never steps back and seriously challenges the premises of the mission. Those who continue to push the Afghanistan mission beyond its narrow counter-al Qaeda foundation do not address how we, as outsiders, can build a functional Afghan state without sufficient buy-in from the various Afghan power-brokers, nor how we can generate that buy-in. Army officers do not reach four stars by telling their superiors “we can’t,” and McChrystal, despite excelling his peers in so many other ways, is no exception. His assessment and the assessments of every other general to manage our longest war have hinged on a prescription for resources and time that take little account of political realities, even if the assessments are accurate in themselves.

I enjoyed reading My Share of the Task for the recap of events that shaped much of my past decade and a half. I knew some of the people who played roles in his operations, I’ve walked the ground he describes, and I was a back-seater in some of the meetings he recounts. It was a pleasant walk down memory lane, but it ultimately disappointed.